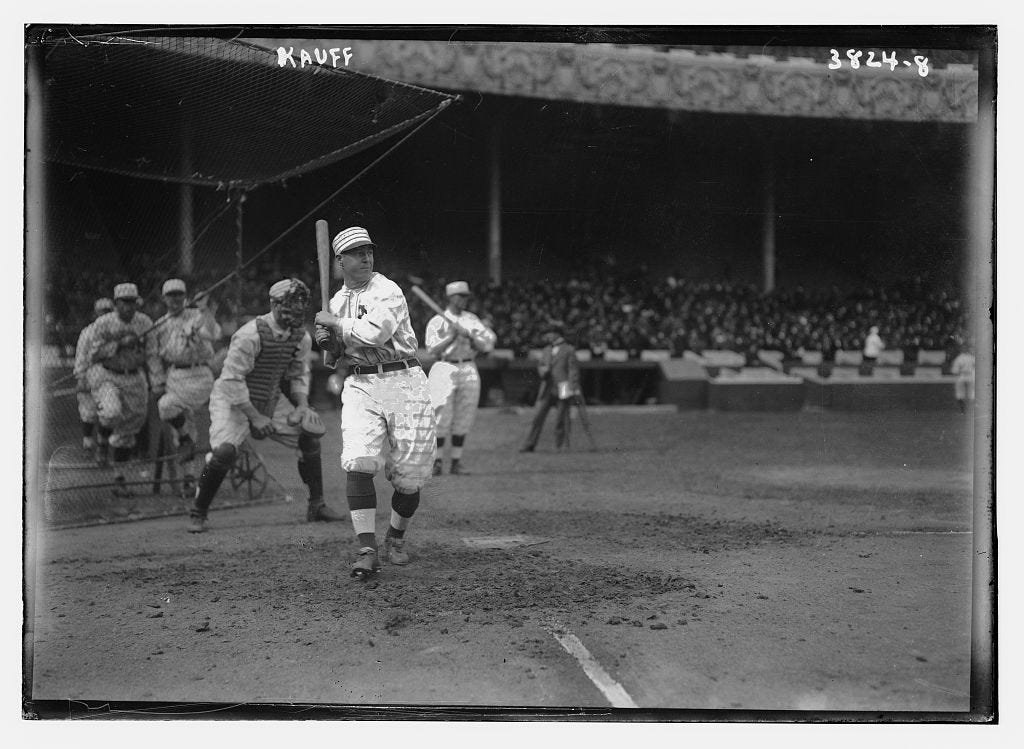

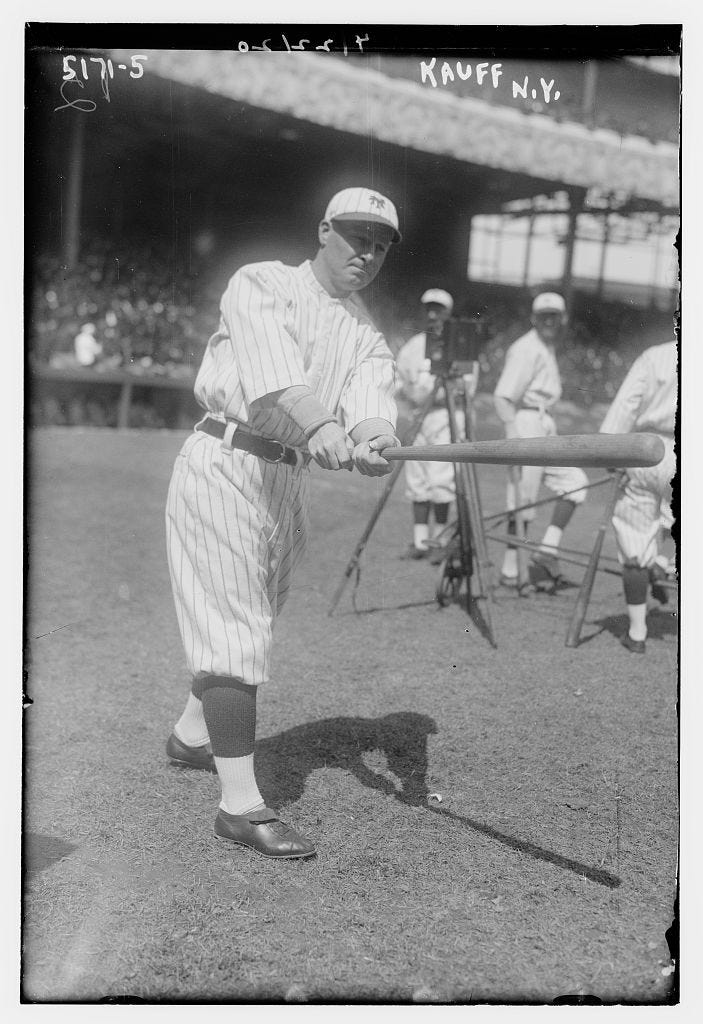

Fate Finally Smiles on Benny Kauff

The Federal League star reinstated 104 years after being given a "lifetime ban"

The big name on MLB’s 17-player newly-reinstated list is Pete Rose, of course. So is “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and the rest of the “Eight Men Out” from the Chicago “Black Sox” of 1919.

On Tuesday, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred officially declared that any “lifetime ban” in MLB is just that- a lifetime ban. After the banned player dies, the ban is lifted, they are reinstated into baseball and become eligible for whatever awards they might receive posthumously- including, obviously, election into the Hall of Fame by the veterans committee (which, by the way, is not scheduled to meet again until 2027, but you have to think that they’ll announce a “special meeting” pretty soon).

But my attention turned to the only player ever given a lifetime ban by major league baseball for something besides gambling. That player is Benny Kauff, and he plays a very prominent role in my book about the 1916 New York Giants and their still-MLB-record 26 game win streak, cleverly titled “26 In A Row.”

Here’s what got Kauff banned from baseball, directly from the book:

“In 1919 Kauff had tried to make some off-season money by starting a car accessories business. Two men who worked for him were accused that winter of stealing a car, repainting it and re-selling it using Kauff’s business as a front. Benny was charged as an associate in the crime but denied knowing anything about it.

Kauff started 1920 once again as (Giants Manager John) McGraw’s center fielder, and the Giants were widely expected to contend for the pennant. But the Black Sox scandal rumors- still just rumors when the season got underway- were dogging baseball, and the car theft charge dogged Kauff. McGraw sent him to minor-league Toronto in July just to get Benny out of the spotlight for a while and to let things calm down.

(In just 79 games with Toronto, Kauff hit a team-leading 12 home runs and led the team with a .343 batting average as they won 108 games, the most in their history- and finished second to Baltimore by a game and a half!)

Obviously, things did not calm down… (and) Kauff nervously paced through the winter of 1920. Commissioner (Kenesaw Mountain) Landis met with Kauff before the start of 1921 and told him that until his case had been decided in the courts, he was ineligible to play ball. Kauff agreed and privately rejoiced, knowing he was innocent. In May, the case went to trial and Kauff was declared innocent in less than a week.

He eagerly waited for Landis to reinstate him. He waited. And waited. He wrote to Landis. He appealed to the newspapers. He tried to be patient.

Finally, Landis announced his judgement: he thought that like the jury that proclaimed the eight Black Sox innocent, Kauff’s jury had been swayed by the star power of a baseball player and justice had not been served.

Landis would serve the justice. Kauff was banned for life from baseball.

Kauff appealed to the New York State Supreme Court, asking them to overturn Landis’ decision. They disagreed with the Commissioner’s decision but declined to interfere as baseball was a “game” and not a “business.” Kauff would never play pro ball again. His career was cut short after just eight seasons. Instead of likely becoming a Hall of Famer, Kauff is now only the face of the Federal League, and even then, that has faded from public memory. He died at age 76 on November 17, 1961.”

With the entire sport reeling from the “Black Sox” scandal of 1919, Commissioner Landis- who was given full power by the owners to “clean up” the sport when he took office- was more than eager to ditch anybody who didn’t live up to his standards, even if the courts declared that man was innocent.

But what becomes clear in looking at Kauff’s story is that Landis didn’t like Kauff well before this. This was Landis’ excuse to get Kauff out of the game, and he took it.

Born in 1890, Kauff grew up dirt poor in Ohio, coming from a family of coal miners, and quit school at age 11 to join them in the pits. When he discovered he could get more for playing one game of baseball than he could for working a week in the mines, his fate was sealed. He moved up rapidly through the minor leagues and made his Major League debut on Opening Day 1912 for the New York Yankees but only played five games before being sent back down. The Yankees were abysmal that year and the next, but Kauff never got another chance with them. He was picked up by the St. Louis Cardinals and assigned to their minor-league team in Indianapolis for 1914.

This is where fate stepped in again and made Benny Kauff a star. A group of rich guys, rebuffed when they tried to buy into the major leagues, took matters into their own hands and created the Federal League, proclaiming it the “third major league.” Major league baseball refused to acknowledge the new league, so the new league began to raid major and minor league teams, paying top-dollar to build their teams- literally- from the ground up.

The Indianapolis franchise did what every other team in the Federal League did, and that was offer every player signed with the organized baseball team in that particular city a chance to jump ship and come play for them. They offered Kauff twice what he was making as a minor-leaguer for St. Louis, and he didn’t hesitate.

A number of established major leaguers jumped to various Federal League teams, legitimizing the league even as major league baseball threatened to ban every player who made the jump. These bans were quickly proven to be farces, as it was realized that players could be used for publicity in whichever league they jumped from or to.

Federal League owners and players also sued MLB to get rid of the “reserve clause,” the famous rule that said that once a player signed with a team, that team owned their rights basically forever. They hoped that a ruling in their favor would legitimize the player raids- and thus, the league.

The suit was assigned to a Chicago circuit court judge who kept delaying making a ruling, figuring that the Federal League would eventually run out of money and patience and settle with organized baseball. That judge was Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Despite Kauff being less established than some of the veterans who made the jump, he quickly became the face of the Federal League. Again, from the book:

“Even if his salary had been quadrupled, it would have been cheap for the publicity Kauff brought the league. He was the best player in the league, and it wasn’t even close. In 1914 he led the league in batting average by 22 points with a .370, and led in hits (211), runs (120), stolen bases (75), doubles (44) and total bases (305). That makes him one of only five players in the 20th century with a season of at least 200 hits, 40 doubles and 50 stolen bases (Ty Cobb did it twice). The “new” statistics show him to also be the league leader by far in WAR (Wins Above Replacement) for position players, on-base percentage, OPS (on-base plus slugging), runs created and offensive winning percentage. The press nicknamed him the “Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” since Cobb was far and away the best player in “organized” baseball and had been for almost a decade.”

But Kauff really wanted to play for the New York Giants and legendary manager John McGraw. He signed a three-year contract with them and jumped back into organized baseball for 1915. But on Opening Day, the Boston Braves refused to take the field against the Giants if Kauff was allowed to play. Kauff and the Giants reluctantly parted ways, and he returned to the Federal League, although this time he was with the Brooklyn Tip-Tops.

Kauff’s trade to the Tip-Tops (the owner of the team also owned the “Tip-Top Bakery”) was a wink-wink deal. Trying to compete with the established leagues by putting two clubs around New York to draw extra publicity, Federal League owners moved the Indianapolis team to Newark, New Jersey, and when Kauff came back they decided that he should play for the team that actually was in New York, and arranged his transfer to Brooklyn. While the Tip-Tops finished 7th, Kauff still led the league in batting average, stolen bases and most other relevant categories, but not at his 1914 levels.

The Federal League finally collapsed after the 1915 season and most owners were allowed to buy into existing MLB franchises in part to prevent them from starting another rival league. Therefore, Landis never had to rule on the “reserve clause,” thus keeping the rule in place across organized baseball. Landis was not shy in letting people know that he believed all the Federal League players were essentially scabs or striking workers who didn’t appreciate what they were being paid by organized teams.

All “banned” Federal League players were allowed back into organized ball for 1916 with one swipe of a pen. Kauff signed with the New York Giants at once (again) and showed up at spring training in Texas in a fancy new car, wearing a bright blue suit with a fur coat, patent leather shoes, flashy diamond rings and stickpin, and $7500 in cash. In his first words to the assembled pressmen, he promised he would do to National League pitchers exactly what he did to Federal League pitchers- in other words, dominate them for years- and all this before he had even taken a single at-bat.

Kauff started slow but came alive in September 1916 and was a big reason the Giants won that record 26 games in a row. (For the details- including the best pitcher in that streak you’ve never heard of, a fellow named Ferdie Schupp- you’ll just have to read the book.)

When the “Black Sox” World Series fixing scandal of 1919 broke in late 1920, owners knew they were in trouble and needed to hire a commissioner, an overseer who would act independently and save baseball, which was suddenly considered very untrustworthy. They remembered the Chicago circuit court judge who delayed ruling on the “reserve clause” just long enough for them to keep all their money and offered Landis carte blanche to rule their game with an iron hand. Landis took all the power they offered and then some more.

So, in 1921, when Kenesaw Mountain Landis had a chance to grind the mouthy former Federal Leaguer under his heel for even being mentioned in the same breath as car thieves, Landis did not miss his opportunity for revenge. Kauff didn’t have a chance.

Kauff played 7 seasons and five games in the majors. His last game was July 2, 1920, just 55 games into his age-30 season. You look at his stats, and they’re pretty good, with the Federal League years standing out. His career batting average of .311 is still good for 108th all-time (just below Ichiro and ahead of Derek Jeter). On-base percentage is .389 and that’s good for 119th all-time (two spots ahead of the legendary Tony Gwynn, admittedly in many fewer games), and his on-base-plus-slugging (on-base percentage and extra-base hits) is .838, good for 241st. There, he’s just ahead of Austin Riley of the Braves, just below Kyle Schwarber and also just ahead of the legendary Kirby Puckett.

Not knowing any of his history, you’d wonder why Kauff’s career just abruptly stops. You’d have to surmise that something weird happened that caused him to quit playing ball. And something did. That something was Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

If he had been cleared, Kauff still probably couldn’t have done enough to make the Hall of Fame by that point- trying to return at age 32 after missing almost two full seasons in an era when most guys were out of the majors by that age. The problem is, he never got the chance to prove otherwise, and he should have. Truthfully, he never should have been drummed out of the league in the first place when it was clear he was not involved with the thieves, which was well before the case went to trial. A hundred and four years later, he is finally clear.

One more Federal League tidbit that I can’t leave out. While some Federal League teams used existing ballparks, the Chicago franchise went full throttle, building a brand-new steel and concrete ballpark in just two months on the grounds of a former Lutheran Seminary on the north side of town. At the time, the White Sox played in still-rather-new Comiskey Park on the south side of town, while the Cubs played on the west side in the aptly named West Side Park, an all-wooden structure that was clearly the third-best park in a now-three-team city.

The press doubted anybody would come to the north side of Chicago to watch baseball because it was “so far away.” But the new elevated rail line was helping the area expand rapidly and the ballpark- placed just blocks away from a stop on the line- was a huge success because the team, nicknamed the Whales, was also a huge success, winning the second and final league pennant in 1915. When the Federal League collapsed, Whales owner Charlie Weeghman was allowed to buy the Cubs and merge the two franchises. Since the Cubs were currently playing in the oldest and worst ballpark in town, he moved them into the new ballpark he had paid for and named after himself on the north side. Soon, Weeghman would go broke himself and sell the team to gum magnate William Wrigley. The stadium was promptly renamed Cubs Park, and after a few years of playing it cool, Wrigley finally named it after himself and his family in 1926.

Thus, Wrigley Field is the last standing Federal League monument.

Benny Kauff’s last major league appearance came on July 2, 1920, in a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds against the Boston Braves, the same team that refused to let him jump back into the majors on Opening Day in 1915. He hit a home run in each game, bringing his season total to three. His very last at-bat was the final Giants plate appearance of the day, and he grounded out.

He was sent to Toronto that night. The Giants had the next day off, played three more games, and then set out on their next road trip. Where did they play that first series on the road without their Federal League star? Baseball fate is a funny thing. You already know.

Fascinating article on a forgotten star.

Thanks foe researching and sharing!

Now, let's get Barry Bonds into the HoF where he belongs.